“Models don’t predict the future. They show the consequences of our choices.”

1. A Beginning in a Brick Building

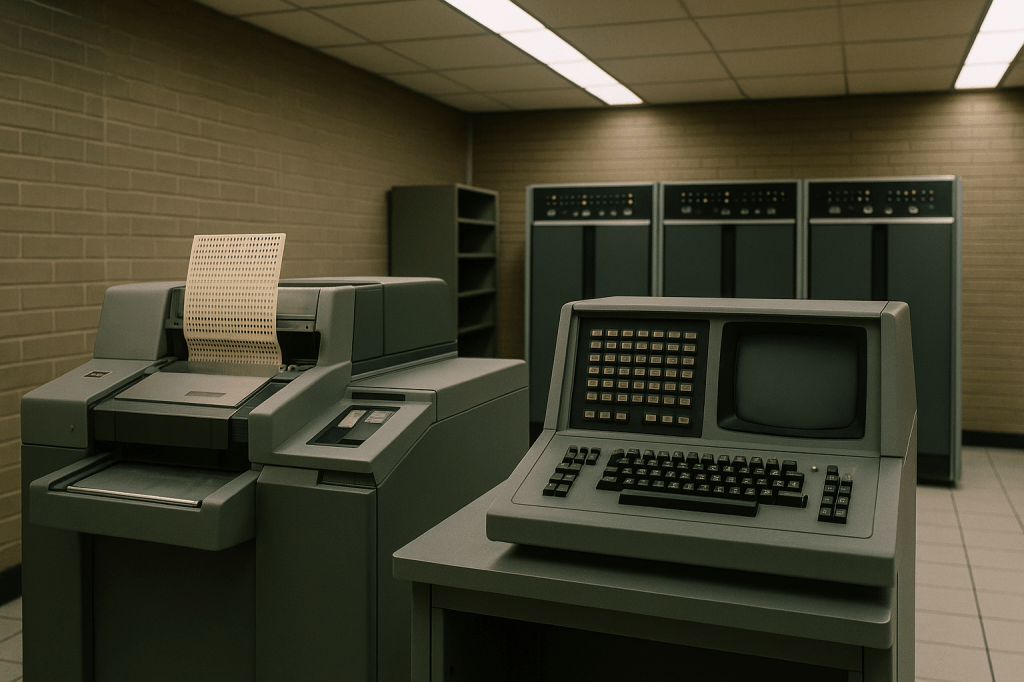

Before most people had seen colour television, in a plain brick building at Princeton’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, a young scientist named Syukuro “Suki” Manabe was doing something almost no one had attempted: he was teaching a computer to breathe.

The room-sized machine in front of him, all vacuum tubes and punch cards, had less power than a modern watch. But inside that limited hardware, Manabe and his team were building something extraordinary — the first model of the Earth’s atmosphere that didn’t just describe weather, but tried to capture the physics driving it.

They weren’t forecasting storms. They were testing relationships: How does carbon dioxide trap heat? How does air circulate? How does the ocean store energy? At first, the computer could only simulate a single vertical column of air. But even that thin slice carried a clear signal of what was to come.

2. What the Early Models Revealed

Manabe’s work showed something simple and unsettling:

add more CO₂ and the planet warms — not evenly, not instantly, but inevitably.

His early simulations produced two insights that remain central today:

- Warming is delayed because the oceans absorb heat before releasing it back into the atmosphere.

- The warming eventually accelerates, because the atmosphere responds faster than the oceans can counterbalance.

Nothing in the model suggested runaway catastrophe. But nothing suggested stability either. It showed a system with momentum — and consequences — that grow with time.

These weren’t guesses. They were physics. And by the late 1960s, the basic shape of our climate future had already been sketched.

3. The Discipline of Modelling vs the Drift of Politics

Modelling relies on assumptions — not guesses, but the baseline values and physical rules needed for a simulation to run. These assumptions describe how the system behaves: how heat moves, how the oceans mix, how the atmosphere responds. They must be transparent, testable, and corrected whenever new data shows they no longer hold.

When a model’s output didn’t match observed behaviour, the assumption behind the mismatch was corrected. Modellers use new data to improve their models. Politicians can use the same data to delay, revise, or undo direction altogether.

This is the difference: modelling improves because each correction builds on what came before. Climate policy, to work, needs that same continuity — a direction that survives election cycles, carries knowledge forward, and doesn’t reset every few years.

The climate doesn’t respond to political shifts. It responds to physics — and to the emissions that accumulate year after year while commitments are debated, reversed, or postponed. The longer we ignore what the data is showing us, the harder it becomes to influence the climate’s future trajectory.

Models improve when knowledge is carried forward; societies do too. When they don’t, the effort required to influence the future trajectory grows with every passing year.

4. The Cost of Ignoring the Long View

Climate change is often described as a future problem, but the delays shaping it happen now. Each year of high emissions locks in more warming, more disruption, and fewer options for managing what comes next. We can’t return the climate to what it once was, but we can influence how quickly it changes and how severe those changes become.

The consequences don’t arrive suddenly. They accumulate: warmer oceans, shifting rainfall, stronger storms, and ecosystems struggling to adapt. Every additional year of elevated emissions raises the baseline the following years must contend with.

That’s why long-term thinking matters. Not because it offers a way back, but because it offers a way to avoid the harsher futures we can still prevent. The sooner nations commit to a clear, sustained direction — and hold it across election cycles — the more room the world has to manage the risks rather than react to them. If we don’t, we leave the next generation fewer choices, heavier costs, and a harsher climate to live within.

5. Closing Reflections — What We Choose to Carry Forward

Manabe’s model wasn’t about prediction; it was about process — update the model’s parameters based on what you’ve learned, correct assumptions that no longer hold, and let the physics show what now lies ahead. It cannot promise 100% accuracy, but it can reveal the range of futures the world may enter, depending on how humanity acts on the information it provides.

Policy needs that same steadiness. Not the illusion that we can restore the climate of the past, but the recognition that each decision shapes what follows. Climate change isn’t a sudden crisis waiting to arrive; it’s a gradual shift already underway, built from decades of choices made, deferred, or undone.

What matters now is whether we carry the knowledge forward — the science, the evidence, the lessons — or continue resetting the puzzle every few years and expect the picture to resolve itself. No single policy or government will determine the outcome, but consistency across time can still meaningfully shape it.

We don’t choose the climate we inherited.

But we can influence the one we pass on — through the decisions we make now and the speed with which we make them.

“The future isn’t set. Our choices decide how it unfolds.”

(Inspired by Terminator 2)

Leave a comment